2023 11 02

Roadmap & Introduction

This piece was written for some discord users who were curious about Anark’s video “Authoritarianism is bad actually“, which is in turn a response to Second Thought’s (JT’s) video “We need to talk about Authoritarianism“. I initially intended to respond to its points rhetorically but it became clear that some of the base facts of the matter needed to be covered, so it is much longer now. What follows is a response to the video along with relatively short analysis of a few projects mentioned in his video.

- Nitpicks

- First I’m going to go over a few smaller points that i thought were worth commenting on, but were not part of core arguments. This way we can get a few things out of the way to allow for a more clear discussion of the core arguments in the video.

- Core Arguments

- Definitions

- the response to On Authority

- the claims of top-down vs bottom-up

- diving into specific projects

- Cuba,

- The USSR,

- China,

- AANES aka “Rojava”, and

- The EZLN.

- wrapping up the specifics to address the real conditions under the lens up top-down vs bottom-up

- diving into specific projects

- Bakunin’s What is Authority

- Is anti-authoritarianism western?

- A short conclusion

Nitpicks

Before we get into the primary content, I’d like to get a few nitpicks out of the way.

Anark says that he agrees with JT’s critique of liberals, that they are being hypocritical when they call places like China and the USSR authoritarian while leaving the capitalist systems they live in unscrutinized. However just after this, Anark turns and says JT’s argument here is “fallacious” and “invalid”. It seemed like he conceded but its not clear if he’s still holding onto this point or not because of the following remarks. I also would’ve liked to see more depth in JT’s video with this part but I think it is understandable for a section aimed at Liberals within a short Youtube video. It does a good job of pointing out how if Liberals applied the lens of Authoritarianism equally/fairly, they would hold different positions than what they do, this leads into a larger point of the shiftiness of the term. More to the point, though I consider this a flaw in the video, JT does acknowledge that the argument is incomplete within the video itself when he talks about how he is trying to add perspective, not engage in what-about-ism. An incomplete argument is not an incorrect one. It would be good and fair to critique this, and expand upon the argument to present it more fully but instead it is pointed out as if it is incorrect and “invalid”, which is unhelpful and takes advantage of the length of JTs video (Anarks is twice as long) to present one of his arguments as incorrect, when its simply presented hastily.

Anark then raises a point that this video seems to have a confused audience, because it spends a long time addressing liberals, and then references On Authority, which is not directed at liberals. He thinks this is somehow confusing or bad. I think this is pretty straightforward considering the video is clearly split into two sections for different audiences where he makes different but related points. Though it may be unusual for a video essay, I do not see it as confusing.

Near the beginning of the video Anark plays a clip of JT in which he shows a dictionary definition of the word Authoritarianism, and he (JT) talks about how this definition fails and is vague. Anark then talks about how JT shouldn’t be using a dictionary definition because it is vague and bad, later going on to say the reason JT’s claims about Authoritarianism fall flat is because of his definition. This really confused me as he seemed to take a definition JT showed as problematic as JT’s own definition of the word, which I do not think was the intent of the definition shown whatsoever.

Anark talks quite a bit in the beginning of the video about how this is in good faith, and he sounds very genuine and I want to believe him but in a later section he says that the purpose of JT’s video is to obscure words that refer to MLs or Authoritarians or whatnot, in the same way Fascists do, because they don’t want people to be able to have the language to condemn them. This seems like a very bad-faith interpretation of the goal of the video. He also talks a lot about how JT either doesn’t know anything about this topic or is intentionally ignoring it. He seems like he is trying to be nice by saying “he probably just doesn’t know” but in fact it undercuts JT’s credibility on topics that he definitely does know about, and in my opinion has legitimate reasons for not addressing by name/in depth in this particular video. I will touch on this later.

Core Arguments

Definitions

Anark defines Authoritarianism as “The degree to which a power structure monopolizes control over the total social implementation of some power”. He also notes that this is not the same as centralization, giving the example that there could be a few different sites of power that each monopolize the power which would generally be controlled by and rooted from the people, but instead is dictated by a small number of power holders and is monopolized by them.

Before moving forward I just want to clarify that even if we assume this definition, it is possible to have something without monopolizing it. Having power or controlling it isn’t necessarily a monopoly, as this power can come from people who give power to it through social practice, among other things. I also would note that in the case of a monopoly held by a power structure, it is not simply the power structure in abstract which holds this monopoly, but the people whom this power structure is accountable and who control it, that has the monopoly (whether that is a small group, or a large group). For a specific example, in undemocratic Neoliberal democracies, it is the Bourgeoisie and state which hold the monopoly, not purely the state in the abstract, as the Bourgeoisie are in control of the state.

This leads into a larger issue with this definition, that is, it only includes state actors, or organizations with a monopoly as “Authoritarian”. Under this definition, the common class collaborationism shown by Fascists with the Bourgeoisie, is not Authoritarian. Fascists have historically held support from confused or privileged groups within the working class, who are not officially affiliated with the Government in any way. Under this understanding of Authoritarianism something like the Charlottesville Unite the Right marches, is not Authoritarian. Despite the fact that white supremacists at these rallies Killed at least 3 people. Similarly, Kyle Rittenhouse, a vigilante with no state connections, shot three people, claiming self-defense for what most agree was premeditated murder. This definition is extremely flawed because of this, as it fails to address seriously violence which is repeated on a large scale but not formally affiliated with any state or monopoly holder. There are many more examples of this violence being extremely “Authoritarian”, without any backing from state groups with a monopoly on violence or power, for more recent examples, look to Israel and the many Fascists who inflict violence without any permission from the apartheid state in the name of self-defense. One may argue that these groups are extensions of the state and follow the same monopoly, but that would mean all it would take is for Fascists to turn against the state for them to no longer be Authoritarian (were the Jan 6th attacks on the US Capital not “Authoritarian”?). In addition to this, Anark did not mention anything about those who follow the ideas of the state or oppression, he only went into the specifics of a monopoly on violence, and taking his definition very literally, not only do these instances not count as Authoritarian, but they undermine the monopoly on violence which a state holds, by performing violence themselves. Which in a twisted way, means that the more common civilian violence is, the less authoritarian a government is.

This should serve as an important reminder that individualist civilian violence is not always justified, and when authors like Bakunin say “In short, we reject all legislation, all authority, and every privileged, licensed, official, and legal influence, even that arising from universal suffrage” (I will go further into this quote later), the implications of this quote are that putting off authority which arises from universal suffrage is part of a struggle for freedom against monopoly and thus should be supported. This contextless support for individualist action is blind to the potential harms of incidents like I mentioned earlier.

Engels is rhetorically addressing two groups at once in On Authority

Anark claims Engels is attacking a straw-man when addressing the need for violence, because “nobody ever conceived that there wouldn’t be a need for violence”. I think this is wrong two-fold. First, Pacifism is a real and present political trend, even Anarcho-Pacifists in particular. I’ve ran into a many groups of people, especially online, who think violence isn’t justified in the pursuit of revolution. Reformists and non-violent Anarchists are definitely a real category of people, though the former is much more common. Secondly, even ignoring the fact that Pacifism is a very real position some Anti-Authoritarians hold, there is something more at play here. Engels is not addressing the need for violence for no reason, or solely to attack Pacifists. He’s doing it to serve a rhetorical purpose. He is setting up a double bind which goes something like this

- If you reject violence as authoritarian, then clearly you hold an unproductive position incapable of enacting real change, because violence is necessary to some degree.

- If on the other hand, you believe that violence is justified in the case of revolutions and to stop Capitalists, then violence carried out by Socialist projects of the past (USSR, Cuba, China, etc) were justified in their rebellion against oppression and pursuit of Socialism. This is not to say that any violence is justified if it simply has good goals, but we have evidence that these projects were largely successful in their good goals, securing a better existence for their inhabitants, as evidenced by several studies and historical documents.

Engels brings these two sides of the coin up as the natural conclusion of either “side” of a common argument against Authoritarianism. If you see it as inherently bad to use “authority” then the position is self evidently wrong, and if authority can be justified, then it is not the presence of authority which makes something bad, but a separate issue that should be discussed specifically. (For example, undemocratic rule) In summary, Engels argument is not a straw-man to address a point which is not held by all Anarchists. It is a rhetorical bind to show the logical conclusion of either position and argue against both to secure each branch of argumentation, even if he recognizes not everybody is to be found in each side of the metaphorical coin, because of course some people will not both be pacifists and justify violence at the same time.

Several times throughout the video Anark talks about defensive violence and impulses of self defense, saying that these are clearly good and justified. This is problematic for a number of reasons, but especially due to the instances of self-defense which we outlined earlier. Self defense is class dependent. If you are a Settler or a member of the Bourgeoisie, an “impulse of self defense” is to protect your spoils of exploitation. He then goes on to ask rhetorically “where are these anti-authoritarian pacifists you seem to be talking about?” in reference to this same argument against On Authority. The reason that many arguments against Anarchists on the subject of authority seem to come across as talking to pacifists, is because “Anti-Authoritarians” often condemn things that were good so fully as to require very sanitized revolutions before they will give support, even sanitizing the projects they support and claim as their own from what the real history tells us. This is something we’ll see later in respect to EZLN and North & Eastern Syria. This dismissal of projects unless their image is so deeply sanitized of all real conflicts is something which can usually go in two directions.

- Create a specific kind of governance or authority which you support and isn’t bad, but deny that the Marxist projects who do this same governance are actually doing so. or

- Instead of creating a specific kind of authority which you support, and potentially letting Marxist projects in, you can instead hide the violence and systemic oppression of your own “Anarchist” projects to portray them as cleaner and less Authoritarian than they really are. I will talk this more fully in a later section.

“State Capitalism”

I don’t have time to fully get into the details of the “State Capitalist” argument, but the next segments will touch on it so i wanted to acknowledge it first. I think the claim that all of the examples of AES as state capitalist is very telling about his understanding of politics and economics, especially class society (he also calls it “red capitalism” like its a serious critique and not some cartoon stereotype). If you want to learn more about this term and its flaws, the Xinhua news agency put out a good rebuttal of the idea that China is state capitalist, and you can find other Marxist critiques on the subject. It’s important to be aware that state capitalism is not something accepted by most socialists and it will come up again later.

Top-Down vs Bottom-Up

A little more than halfway through the video, Anark claims the difference between Anarchist movements and Marxist ones is if they are organized formed from the bottom up, or the top down. Setting things up with this wording paints a very particular picture of the differences between the projects of these two groups, and makes it extremely easy to fall on the side of disliking Marxism. I want to ask however, is this wording truly representative of reality? Is it an accurate description, or one meant to signal certain virtues to Anarchists while demonizing Marxists? Let’s look over the realities of some of the projects involved in this discussion.

How does Cuba, USSR, China, etc… work?

Cuba

I will start with Cuba, since it is one which I am most familiar with. Lets dive into their elections and power-structure.

Elections in Cuba take place every 5 years. It is not required to be a party member to be a candidate nor to be elected in a Municipal election, anyone over 16 is eligible both for voting and nomination as a candidate for a delegate position. One interesting thing about Cuban elections is that the candidates aren’t allowed to campaign for office in any way similar to what we’re familiar with in liberal democracies. There are boards which have equal space for candidates and have pictures of the candidates and a list of their policies.

Anyone over 16 can both vote and be nominated as a candidate. Cuba also holds the 3rd highest percentage of women in Governmental positions of any country. The Municipal election process in Cuba can be considered a direct democracy. The municipality elections are a very important aspect of how their elections differ from liberal elections but they’re covered well in many other existing works like this video, which I highly recommend. These elections are quite well done and democratic, this aspect of their democracy is rarely contested.

The main contention with Cuban democracy comes from higher organs of government. The claim is generally that while the municipalities are good, they have very little control over higher government because the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) picks the candidates for their higher assembly and then elections are held. The reason people see this as a problem is that you either vote for the person or you don’t, you don’t vote for opponents. The number of candidates chosen is the same as the seats available, this is often misunderstood as meaning the party has complete control over the higher organs of government, since they pick the candidates, thus making it undemocratic.

We immediately run into two issues here:

- Though the candidates have historically always been elected and put into those positions, the list of candidates isn’t just made by the PCC. It has to approved by the municipalities, which most already agree are democratic, as I stated earlier.

- The PCC isn’t a malignant party, nor are they undemocratic. Its made up of workers unions and proletarian movements. It includes the main woman’s rights organization in Cuba as well as student organizations, on top of their workers unions.

These two things mean that even though the Provincial Assembly nominees are nearly guaranteed office as the elections are not competitive, the way the nominations are made is through a workers party in collaboration with the democratically elected municipality delegates. Another thing which is really significant about the power-structure in Cuba is their recall process, which can be thought of as a sort of “impeachment” but one which actually works. If an elected official does something their electorates dislike, or abuses power, they can simply be recalled by their electorates. The main three points I want to stress here are as follows:

- Capital is not allowed in campaigning, nor in the positions themselves (Municipal delegate is an unpaid position, with related expenses being covered by the Government).

- They have average voter turnout of 86.19%, (in 2005 it was 97%),

- Delegates have regular meetings with their electorates and can be recalled at any time, and

- Vote counting is open and can be watched and monitored by anybody who wants to.

What non-competitive means in practice:

“Voters can select individual candidates on their ballot, select every candidate, or leave every question blank, with no option to vote against candidates. Although there is only one candidate per seat, candidates must still obtain the support of 50% of voters to be elected. If a candidate were to fail to garner 50% of the vote, a new candidate would have to be chosen. However, this has never occurred.”

As we can see, Cuba has a working democracy with almost 100% of the population represented in their elections, they also have functional recalling of representatives who the people feel no longer deserve to represent them, for whatever reason that may be.

Is Cuba a successful country? Is it an authoritarian or anti-authoritarian one? Is it top-down, or bottom-up?

USSR

Next, lets cover how the Government in the USSR worked.

The USSR stands for United Soviet Socialist Republic. Soviet refers to Worker’s Soviets, with the word itself literally translating to “Council”. Soviets were (as implied by the name) councils of workers who met to discuss matters relevant to those workers. Every 2 years the local soviets elected an executive committee, which would represent the workers, and participate in administrative duties. In case of any issues, these committee members were recallable much in the same way Delegates in Cuba are today, they also only served for 2 years at a time, until the next election. To be elected, people were nominated and voted on by large groups of the population. Workers cooperatives, unions, party members, youths, military members, women’s groups and others all weighed in on who to nominate and serve in the committee, it was not some exclusive group of prestigious workers. Opposing parties were not allowed, but affiliating with the communist party was not required, and unaffiliated/independent members were common. Soviets used direct election systems, where you voted for who you wanted to represent you, rather than voting to have some kind of unelected electoral college then vote in your place.

These elections worked their way up the chain of Soviets. From local soviets, to city soviets, all the way up to the Supreme Soviet, which had two “Chambers”. First was the Soviet of the Union, which held 1 deputy per 300,000 people, elected every 4 years. The second was the Soviet of Nationalities, which held 25 deputies from each union, 11 for each autonomous republic, 5 for each autonomous region and 1 for each national area. The soviets were split this way to give different nations, ethnicities, and oppressed peoples the right to self determination and the ability control the laws relating to their areas. This helped immensely with cultural preservation and independence. Border unions were also given the right to succeed and become their own distinct nations. This is actually in part why Ukraine is a nation today, where it was previously part of the Russian Empire, since it was given status as a Union and allowed to become independent, it did so after 1991 following the collapse of the USSR. People often forget just how many countries were within the Russian Empire (Hence why it was called “Prison of peoples” by Engels and later Lenin) and how many were allowed self determination following the Russian revolution.

The USSR also had an organ called The Council of Peoples Commissars, which was a group of groups all with their own jurisdiction and responsibilities. Some examples of Commissars include, among others:

- the State Planning Commission

- the Procurement Committee

- the Committee on Arts

- the Committee for Higher Education

As we can see, these Commissars handled quite the range of responsibilities, and not everything was ran all by a singular group. Where singular groups formed, they were made up of representatives from lower level groups. whether that be from the local soviets, members of People’s Commissars, or City level Soviets, they were all representatives brought forth from lower organs of government and recallable from their positions.

There is also the famous quote where the CIA themselves admit that the USSR had collective leadership:

“Even in Stalin’s time there was collective leadership. The Western idea of a dictator within the Communist setup is exaggerated. Misunderstandings on that subject are caused by a lack of comprehension of the real nature and organization of the Communist power structure.”

It is also worth mentioning the many accomplishments of the USSR including primary responsibility for stopping the Nazis, to vastly increasing calorie intake, education, medical care, and housing. This study, which covers several socialist states including the the USSR, Cuba, and China, found that “the socialist countries have achieved more favorable PQL [physical quality of life] outcomes than capitalist countries at equivalent levels of economic development.”

Was the USSR a successful country? Is it an authoritarian or anti-authoritarian one? Is it top-down, or bottom-up?

While many do consider the USSR a success in moving the socialist movement forwards (myself included), it did eventually fall, so lets move on.

China

Briefly, I will cover some aspects of China.

Anyone over 18 can vote or stand in election. The National Peoples Congress (NPC) is the head of legislation in China. Members are elected directly into the NPC by voters, though they do not determine the position members hold within the NPC. Higher positions within the NPC are then elected from those who have been voted in as representative members. Source

According to a survey conducted by Harvard from 2003-2016: “in China there was very high satisfaction with the central government. In 2016, the last year the survey was conducted, 95.5 percent of respondents were either “relatively satisfied” or “highly satisfied” with Beijing.” The authors publishing the survey say that this is likely due to the constant growth and improvement in conditions in China.

“We tend to forget that for many in China, and in their lived experience of the past four decades, each day was better than the next.”

This is backed up by data, for example China says 98.99 million people in countryside have been lifted out of poverty in the last eight years, which can be source checked via the world bank, showing that this is indeed the case.

It is also worth mentioning there is no private ownership of land in China. Though the constitution mentions protecting private property, it is specifically referencing “the right of citizens to own lawfully earned income, savings, houses and other lawful property” as referenced in the pre-2004 constitution. This includes things earned by individuals, and is not protection of Capitalists

A common retort to this and the idea that China is socialist more generally, is the fact that they have billionaires. I will not cover this here but you can read about it and the issues with this line of argument here.

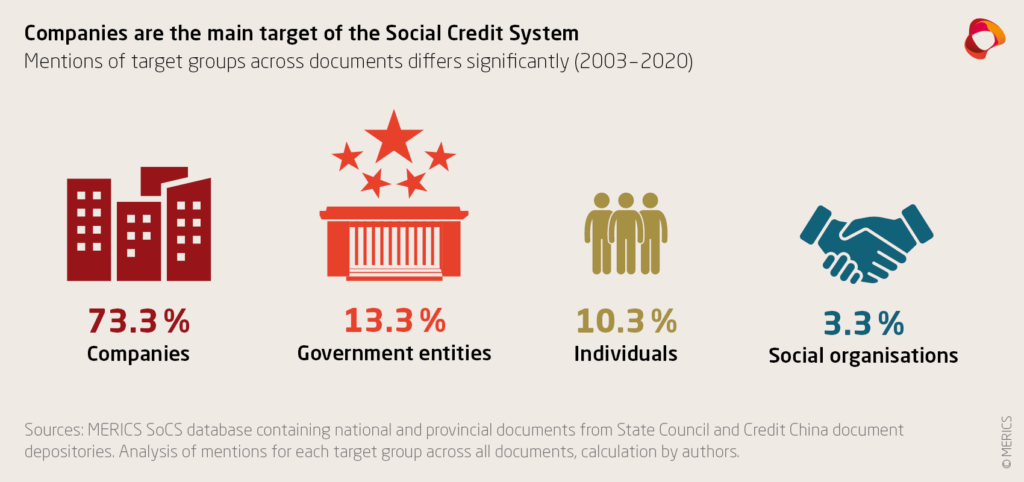

What about social credit? Social credit is primarily enforced on businesses, only 10% of targets are individuals, with the other 90% being primarily Companies, followed by government and social organizations. It also rarely blacklists at all, with only 1-2% of companies (the largest group) being blacklisted per year.

This is a system for a governing body (the organized masses) to enforce its will on Capital, not a way for Capital to enforce its will on the government, or even individuals.

Is China a successful country? Is it an authoritarian or anti-authoritarian one? Is it top-down, or bottom-up?

How does Rojava, the Zapatistas, etc… work?

Rojava

This section is by far the longest, as we do not have the kind of sources and academic studies we do with China, Cuba, and the USSR which show their successes. It is also the project which I find is the most misunderstood, so I have devoted quite a lot of space to it. For more information on this topic the following articles provide an in-depth and helpful history of events which I highly recommend reading in full, they were instrumental in the writing of this section. Romancing Rojava: Rhetoric vs. Reality By Joshua Landis, and On Rojava and the Western Left By the Line Struggle Collective)

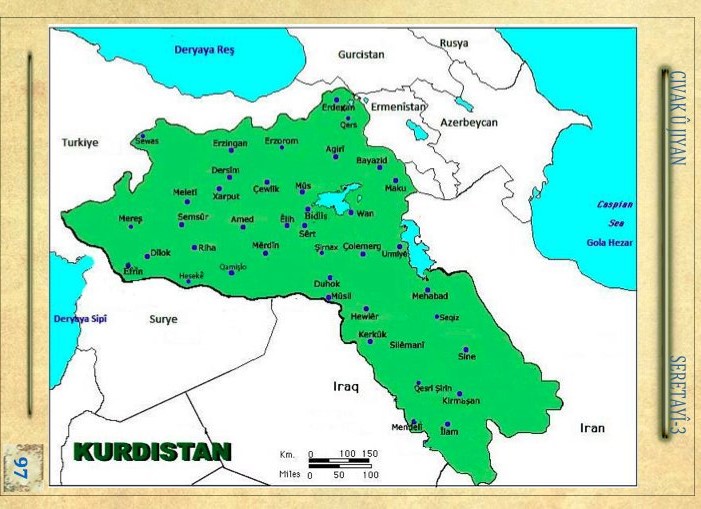

“Rojavayê Kurdistanê” or Western Kurdistan, often shortened to simply “Rojava” refers to movement for national independence of Kurds in North and East Syria. The technical name for this project is The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

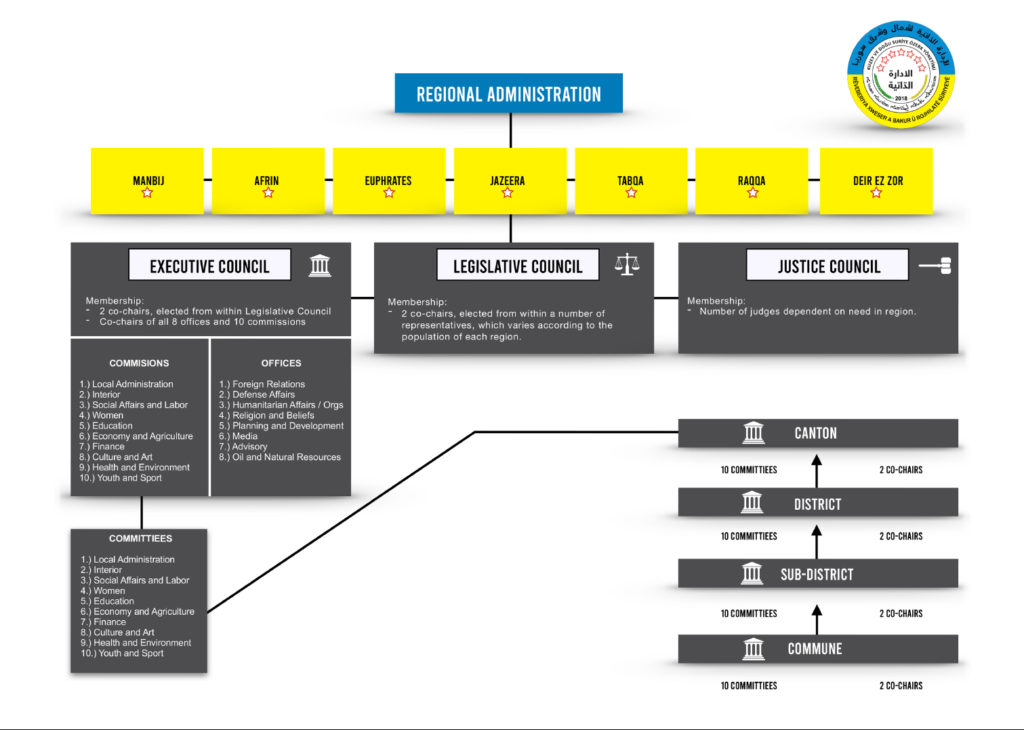

The Governmental structure is as follows, from Syrian Democratic Council (Emphasis my own)

“Executive Council: The Executive Council (EC) consists of two Co-Chairs, ten Commissions, and eight offices. The EC oversees and coordinates the work of the commissions and offices in each of the regional administrations. The EC sets the budget for each region.

- The Commissions: Local Administrations, Interior, Finance, Education, Health and Environment, Economy and Agriculture, Women, Social Affairs and Labor, Culture and Art, Youth and Sport.

- The Offices: Foreign Relations, Oil and Natural Resources, Humanitarian Affairs and Organizations, Religions and Beliefs, Defense Affairs, Planning and Development, Media, Advisory.

Legislative Council: Two Co-Chairs are elected from within 70 representatives. The Legislature comprise of 49 Representatives (seven from each of the seven regions) and 21 Technocrats (experienced legislators). Justice Council: [Also called the General Council for AANES] The Council consists of two Co-Chairs, elected from within 13 judges. All judges are elected from their regional justice councils. It is the highest judicial authority in the AANES. It organizes and supervises the justice institutions in the seven Regional Administrations. This Council does not see cases nor interfere in the courts of the region. It deals with legal conflicts between the regions.”

Regional governments follow much the same structure, being elected up the chain from neighborhood level local Communes, to local Councils, Districts, and finally Cantons, as shown in this graphic from the Syrian Democratic Council website.

The problem with this analysis is that it is very surface level and the real world governmental systems are complex and changing rapidly as this is a very volatile project and area. Unfortunately, more details are scarcely available for the project. For example, the “21 Technocrats (experienced legislators)” are not talked about anywhere else that I am able to track down, except for the SDC wikipedia page, in which it cites three dead links on the subject. This is an issue because having technocrats in your legislative council means that your government is run by those who hold high positions in the related field and not those who are elected. This is quite similar to the accusation of “career politicians”, of those in the USSR, especially during the later parts of its lifespan.

In spite of a lack of English resources on the topic, many claims of positive outcomes and decentralized, non hierarchical, anti-authoritarian governance are made. How true are these claims? It is difficult to make hard claims about their governmental structures due to the lack of proper documentation. However, we’re not without resources to learn more about the AANES, as there are many primary sources for things happening on the ground under this governing system.

So then the question becomes, what is it like in “Rojava”? how is this system treating the people who live in North East Syria?

The first important thing to note is that Rojava is a Kurdish Nationalist movement. This is why it is so often referred to using the Kurdish word for West, despite being the East of Syria. This alone is not proof of it being a nationalist movement but it should tip us off to the possibility, we will see more of this as things progress. Additionally, nationalism is not an inherent wrong. Nationalism of indigenous peoples against oppressors can often be a progressive force: current Palestinian actions against Israel for example, may take on a nationalistic character in certain circumstances but this is a progressive nationalism which serves to fight colonialism and for self determination of their people. Advocates of AANES often do their best to portray it in this light an indigenous movement, fighting against Turkiye for the benefit of all on the land.

The SDC website claims:

“The AANES constitution protects the rights of all to believe and worship as they wish, and mandates that each political position in the regional government, local councils, and villages be held by individuals from two distinct cultural and/or religious backgrounds. The constitution guarantees full rights to minority groups and protects them from persecution. The SDC and the AANES councils actively seek roles for minority group leaders and guidance and participation from them.”

However, the reality is quite different. In practice this entails a segregation between religious and ethnic groups. The education in AANES for example, was split by the PYD (Democratic Union Party) into groups for each religious-ethnic minority. This was allegedly done to allow each group to learn in their native language. However, the curriculum itself was Kurdish nationalist, with native Assyrians saying “We’ve merely been granted the right to learn about Kurdish history, from a Kurdish nationalist perspective, but in our own language”. Some of the curriculum can be seen in the article Romancing Rojava which I mentioned earlier.

This change to the curriculum was rejected outright by the Assyrian community, both due to the issues with curriculum and the dangers of ethnic segregation. Tensions got so bad that when schools in Qamishli disregarded the Kurdish Curriculum and taught instead Syrian Curriculum, not only were they forcible shut down entirely, with all teachers and staff being fired and all locks being replaced, but when resistance inevitably occurred, bullets were fired into the sky during large protests, and teachers were brutalized almost to the point of death (video evidence after the fact, blood but no violence is shown)

Additionally, Solueman Yusph an Assyrian Journalist was arrested by the PYD forces (SDF) for reporting on the school closures. Yusph corroborates the hospitalization by the SDF of the teacher from the video source above, Isa Rashid. He also spoke out against the displacement of Native Assyrians from their homes by Kurdish Nationalists.

Following this, 16 Assyrian-Christian groups spoke out in a joint letter against the pressures on native Assyrians being relocated by the Rojava government. The only local “Assyrian” group which did not denounce the pressures faced by these schools and displaced Assyrians, was the Dawronoye, a group which is directly affiliated with the PYD. The Dawronoye and the Syriac Military Council (MFS) under it are supposed to represent Assyrians within Rojava, despite this the MFS can hardly be said to represent anyone but the Kurdish Nationalists they repeatedly show allegiance to. This group is compared by some to the pro-diversity stances of Western Militaries, in particular the US military and its recruitment of minorities to do its dirty worker under a veil of progressive attitude.

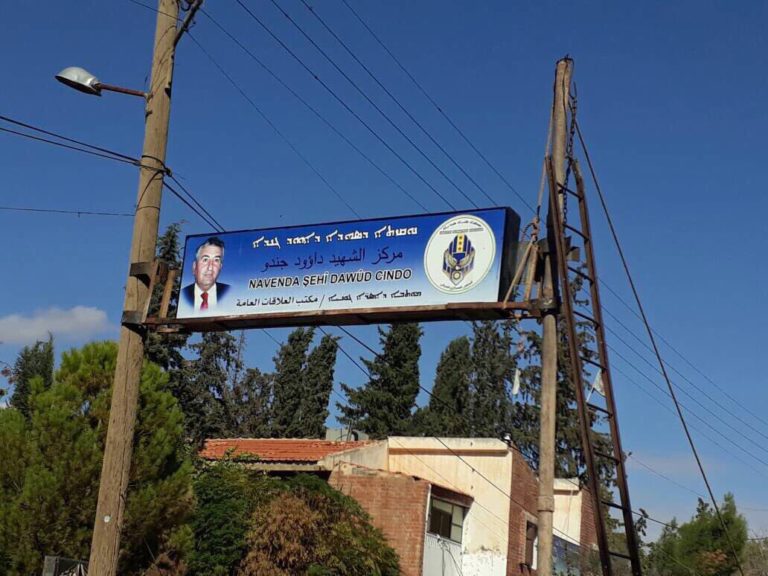

To further illuminate these conditions, lets look over a particular incident which I believe encapsulates the issues. In 2015, a man named David Jindo was murdered by the YPG (A militarized group under the PYD). David Jindo was a leader of a small defense group which protect an Assyrian town from ISIS. This group was originally willing to work with the Kurdish YPG but the YPG pressured the local defense forces to not only work with, but work under the command of the YPG and MFS, taking orders from them, and join the fight for “Rojava”, else leave Syria. As the group continued to refuse these demands the Kurdish forces (including the allegedly progressive MFS) began to loot the area regularly. Jindo, who had already come under fire for refusing to use the term Rojava, insisting on using other terminology, submitted several requests to leadership for help. Instead of receiving help, YPG forces assassinated him, and tried to kill his acquaintance Nasser, who barely survived and unable to talk, wrote the details of the incident from while hospitalized, confirming these events.

Despite being killed by the YPG and MFS, Jindo was later appropriated for MFS messaging, being upheld by them as a matyr for their cause, when they are the very ones who killed him.

This is not an isolated incident, merely a particular example. Raids and lootings by the SDF are not exceptional and you can read about other instances, like one from 2021 where eyewitnesses said “forces consisting of several cars raided civilian homes, without warning, accompanied by indiscriminate shooting between the houses with the aim of terrorizing the ‘wanted’”. During this attack, an innocent man and his son were shot dead causing civilians to flee, who were then open fired on, killing 2 more. These attacks are “often supported by US attack helicopters”.

Lastly before closing up, lets touch on the global politics and public relations of the AANES.

Most people who discuss the topic of Rojava are aware that the U.S. has allied themselves with Rojava and supplied weapons to the project. The usual talking point in regards to this is that the YPG and related forces are fighting against ISIS and this benefits the US as well. It is terrible for image, but the enemy of my enemy is my friend. So goes the reasoning. However, this is not the only reason for US support of Rojava. Following talks of no longer providing assistance to Rojava, A National Security Council Official publicly stated that they believe support should continue, as “It [Rojava] would be another Israel in the region”. This statement may sound strange to many who are familiar with Rojava as an Anarchist libertarian project, but knowing the treatment of the indigenous Assyrians in NE Syria, this makes much more sense. Additionally Israel themselves see Rojava as an ally, and even then Syrian government itself calls out ties between Rojava and Israel

We also see Rojava-Israel parallels in this article, detailing how Assyrians are made “Strangers in [their] own homes” from Kurdish occupation. The joint letter from earlier which only the Dawronoye did not co-sign, was spurred on by a law which removed property from displaced Assyrians and reappropriated their ownership to the PYD. This is almost exactly how property is stolen from displaced Palestinians in Israel, under the Absentee Property law. As is pointed out by the Line Struggle Collective piece on the topic, it is worth remembering that many communists initially supported Israel despite its colonialism, due to the minorities which it was composed of and the workers co-operations present.

On the topic of reappropriating land, the AANES constitution article 43 also explicitly protects private property. This alone is not necessarily indication of a reactionary policy towards land and property as mentioned with respect to China. However, it is made clear that land reform is an extremely low priority, if one at all for those in the AANES. “For Öcalan, socialism and workers’ struggles are of secondary importance compared to questions of religious and ethnic identity and democratic freedoms. This assessment seems to be shared by many of his followers. When a group of German leftists visited North Kurdistan to see the system of democratic autonomy ’in practice,’ a topic like land reform was not even discussed”. From libcom.org (as outlined by the line struggle collective piece.)

The Rojava project is specifically working for autonomy before any kind of land reform, or disenfranchising of the Bourgeoisie. This is not inherently bad, but does make a society more difficult to transform, and makes the following information even worse news.

On October 22, 2019, following many negations and peace talks facilitated by Russia, the Second Northern Syria Buffer Zone was established, confirming the role of the Syrian Government in the governance and defense of Syria’s northern border. The SDF stated that it was ready to consider merging with the Syrian Army following the adoption of a political settlement, and Russia sent military police and heavy equipment to help implement the deal. The AANES is now allied with the Syrian Assad government which they originally stood against, along with Russia who poses problems for reasons I wont get into here.

Is this a successful project? Is it an authoritarian or anti-authoritarian one? Is it top-down, or bottom-up?

The Zapatistas/EZLN

The Zapatistas of EZLN are fairly forward in their communications and I don’t contest much of their statements, so we can see from their releases what they say about their structures and Anarchism vs. Marxism. Much of this section is from The Nature of The Zapatistas by Nodrada, as their piece is well researched and this section is not the primary point of this response, but a necessary precondition to understanding the topic

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation, or EZLN are a group organizing for better conditions in South Eastern Mexico, fighting against a corrupt government and taking control of areas in the Chiapas region. The EZLN territories include approximately 300,000 people.

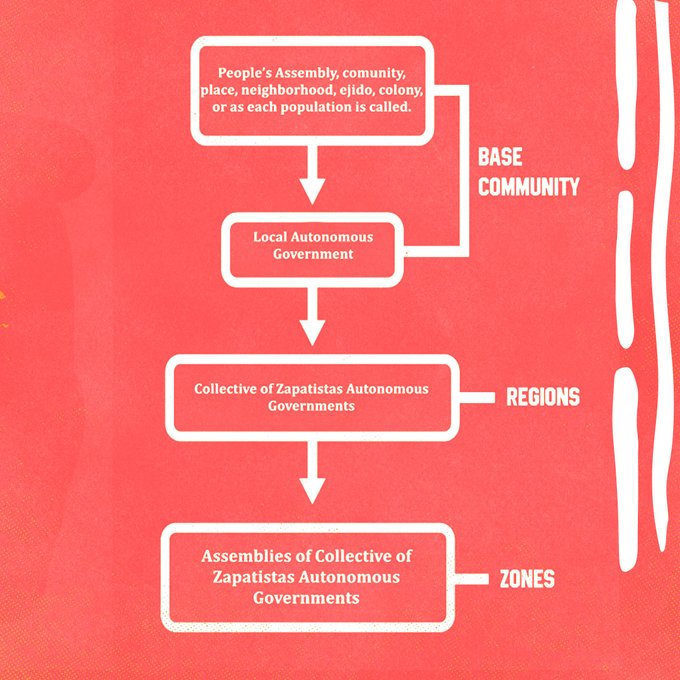

As of November 2023, the Zapatistas have restructured their system. The new structure can be found here but I will summarize:

The Zapatisas are organized into groups called GALs (Local Autonomous Government). There are many of these (thousands), but they all come together under what are called CGAZ (Zapatista Autonomous Government Collectives). Authorities are called from the GALs under a CGAZ for assemblies, these assemblies discuss things such as health, education, justice, commerce, etc… Whatever policies are proposed and decided upon are then monitored by CGAZ level coordinators. There are also The Assemblies of Collective of Zapatistas Autonomous Governments, called ACGAZ. The ACGAZ meet to preside over the affairs of zones (collections of CGAZs) but are held accountable to the GALs and their CGAZs to meet all the needs of each local area.

This structure is very democratic but it is not particularly exceptional among what we have discussed. It follows along very similar lines to earlier projects mentioned, small local groups organize and send representatives to higher level organizations which are held accountable to the lower branches whom they represent. Nodrada, a Marxist author writes:

“The EZLN’s ideological orientation is clearly not as unprecedented as the Western press has sought to portray them. Although they emerged in 1994, after the fall of the Eastern Bloc and the temporary ideological “death” of Marxism, they are not anti- or non-communist. It is true that they do not set socialism their immediate aim. However, they do not reject revolution. Instead, they have long been trying to overthrow the corrupt, US-aligned PRI bureaucracy of Mexico in favor of a democratic, social republic. They make this clear in the First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, saying:

“We declare that we will not stop fighting until the basic demands of our people have been met by forming a government of our country that is free and democratic.”

It is possible that they consider the goal of socialism to only be possible given these conditions. There is a long history of Marxists setting national liberation from imperialism and the construction of an independent democracy as their short-term aims. This has been true from the early Communist Party of China, to the Iraqi Communist Party, and even to Mexico’s own Communist Party. The key distinction is that the EZLN seeks to build a broad front specifically for this aim.”

It is perhaps partially for this reason then that they have faced harsh criticism from within the Anarchist community. One Anarchist notable for garnering a response from EZLN members wrote:

(emphasis my own)

“They [EZLN] speak repeatedly of the “right to freely and democratically elect political representatives” and “administrative authorities”. And the goals for which they struggle are “work, land, housing , food, health care, education, independence, freedom, democracy, justice and peace”. In other words nothing concrete that could not be provided by capitalism. Nothing in any later statement from this prolific organization has changed this fundamentally reformist program. Instead the EZLN calls for dialogue and negotiation, declaring their willingness to accept signs of good faith from the Mexican government. Thus, they send out calls to the legislature of Mexico, even inviting members of this body to participate in the EZLN march to the capital, the purpose of which is to call on the government to enforce the San Andres peace accords worked out by Cocopa, a legislative committee in 1995. So we see, regardless of the fact that they are armed and masked, the EZLN is a reformist organization. They claim to be in the service of the indigenous people of Chiapas (much as Mao’s army claimed to be in the service of the peasants and workers of China before Mao came to power), but they remain a specialized military organization separate from the people, not the people armed.“

The response from EZLN members was quite clear.

“(…) the article entitled “The EZLN Is NOT Anarchist” reflected such a colonialist attitude of arrogant ignorance, several of us decided to write a response to you.

You are right. The EZLN and its larger populist body the FZLN are NOT Anarchist. Nor do we intend to be, nor should we be. In order for us to make concrete change in our social and political struggles, we cannot limit ourselves by adhering to a singular ideology. (…) We may be “fundamentally reformist” and may be working for “nothing concrete that could not be provided for by capitalism” but rest assured that food, land, democracy, justice and peace are terribly precious when you don’t have them. Precious enough to struggle for at any cost, even at the risk of offending some comfortable people in a far off land who think their belief system is more important than basic human needs. Precious enough to work for with whatever tools we have before us, be it negotiations with the State or networking within popular culture. Our struggle was raging before anarchism was even a word, much less an ideology with newspapers and disciples. (…) The struggle in Mexico, Zapatista and otherwise, is a product of our histories and our cultures and cannot be bent and manipulated to fit someone else’s formula, much less a formula not at all informed about our people, our country or our histories. You are right, we as a movement are not anarchist. We are people trying to take control of our lives and reclaim a dignity that was stolen from us the moment Cortes came to power.”

EZLN has also had a long history involved in the Marxist tradition. This is not to say that the Zapatistas are Marxists but they are far from Anti-Authoritarians. In particular, the Zapatistas arose out of the Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional (FLN) who were explicitly Maoist in political orientation, though the term Zapatismo predates it to other Marxist and Anarchist revolutionaries. the Zapatistas align themselves with Cuba and claim Che Guevara (A Marxist-Leninist) as a hero.

Though critical of vanguard parties, this is nothing new within even Marxist circles. Mao in particular had many criticisms of vanguard parties and it makes sense that the Zapatistas follow such criticisms considering EZLNs focus on mass line over sectarian identities, as well as their history growing out of Maoist organizations. Che Guevara was also at times critical of vanguardist ideas. This context brings a different light to the common criticisms of “vanguardism” from those within EZLN. Knowing the history of EZLN, these critiques likely stem from within the lineage of Marxist movements, rather than a denouncement of it from an outsider who positions themselves against Marxism. Ultimately the Zapatistas are neither a bastion of Marxism-Leninism, nor a icon of Anarchism. If I were forced to name them ideologically, I would likely say are inline some branches of Maoism, however I believe it is better to not place our own labels on their movement and instead view them for their practices and goals.

It is unfortunate to spend so much time on addressing speculation surrounding the ideology of EZLN but it is unavoidable considering the amount of groups which claim EZLN as their own. It does however, make sense that groups would claim ideological responsibility for EZLN as they have had great successes in several areas. From food to medicine to political representation, the Zapatistas have brought many wins for the indigenous people in and surrounding Chiapas.

The healthcare and education have improved drastically in the Chiapas region due to the presence of the Zapatistas. From, Understanding Zapatista Autonomy: An Analysis of Healthcare and Education:

“it is clear that community residents unite together to devise education policy for their children. They design the style of curriculum to be offered in the local school house and select and appoint the education promoter to teach the chosen subjects. Such a community oriented approach to education guarantees that indigenous culture and language remain a priority on the education agenda in Zapatista communities. (…) Widespread acceptance of autonomous healthcare in all 1,111 Zapatista communities makes it an important pillar of Zapatista autonomous development. The positive benefits to health experienced by the communities indicate that this approach to healthcare has proven to be successful. The health of Zapatistas, particularly of women and children, has significantly improved throughout all communities. Statistics clearly show the growing numbers of women and children now surviving childbirth.”

Is this a successful project? Is it an authoritarian or anti-authoritarian one? Is it top-down, or bottom-up?

Following these examinations, we can see that these projects are actually quite similar in many ways. The projects claimed as Anarchist are not uniquely libertarian are they? Of course, the Marxist projects mentioned do have issues, plenty in fact, but so do all projects. Looking at the structures, however, where is the difference which makes one group so Anarchist and Libertarian, while the others are authoritarian nightmares? In reality the structures of these projects are actually quite similar in many ways. This is why Engels says in On Authority

“When I submitted arguments like these to the most rabid anti-authoritarians, the only answer they were able to give me was the following: Yes, that’s true, but there it is not the case of authority which we confer on our delegates, but of a commission entrusted! These gentlemen think that when they have changed the names of things they have changed the things themselves. This is how these profound thinkers mock at the whole world.“

Engels highlights the usage of different labels and terminologies for structures which are in reality, not qualitatively different. This section is also partially a response to Bakunin’s “What is Authority?“, which Anark states is “A refutation of On Authority written by Bakunin a year BEFORE On Authority was even published”, here is a portion from Bakunin for reference before we continue:

“Does it follow that I drive back every authority? The thought would never occur to me. When it is a question of boots, I refer the matter to the authority of the cobbler; when it is a question of houses, canals, or railroads, I consult that of the architect or engineer. For each special area of knowledge I speak to the appropriate expert. But I allow neither the cobbler nor the architect nor the scientist to impose upon me. I listen to them freely and with all the respect merited by their intelligence, their character, their knowledge, reserving always my incontestable right of criticism and verification. I do not content myself with consulting a single specific authority, but consult several. I compare their opinions and choose that which seems to me most accurate. But I recognize no infallible authority, even in quite exceptional questions; consequently, whatever respect I may have for the honesty and the sincerity of such or such an individual, I have absolute faith in no one. Such a faith would be fatal to my reason, to my liberty, and even to the success of my undertakings; it would immediately transform me into a stupid slave and an instrument of the will and interests of another. (…) I bow before the authority of exceptional men because it is imposed upon me by my own reason. I am conscious of my ability to grasp, in all its details and positive developments, only a very small portion of human science. The greatest intelligence would not be sufficient to grasp the entirety. From this results, for science as well as for industry, the necessity of the division and association of labor. I receive and I give—such is human life. Each is a directing authority and each is directed in his turn. So there is no fixed and constant authority, but a continual exchange of mutual, temporary, and, above all, voluntary authority and subordination.”

And then concludes that:

“In short, we reject all legislation, all authority, and every privileged, licensed, official, and legal influence, even that arising from universal suffrage, convinced that it can only ever turn to the advantage of a dominant, exploiting minority and against the interests of the immense, subjugated majority.

It is in this sense that we are really Anarchists.”

In this passage Bakunin states that he will accept authority if he himself determines it to be legitimate, but will not recognize authority as legitimate even if it is arrived at through universal suffrage. This is simply individualistic, anti-social behavior, rejecting democracy only in favor of ones personal views.

Engels’ passage from On Authority also addresses something which I will address later, in relation to the Spanish Bakuninists. When I come back to this it will tie the section together neatly, so bare with me.

If these projects are structured so similarly, why would one claim Marxist projects to be “top down”? aside from simple propaganda? Things usually do not stem from nowhere, even propaganda usually has a basis in something real, so I looked into this particular argument and found a very similar argument to Anark’s being made on a popular QnA on the Anarchist Libraray. This section Titled “Is Leninism Socialism from below?” Cites Lenin from On the Provisional Revolutionary Government (Collected works of Lenin, volume 8, page 474), specifically a section titled “Only from below, or from above as well a below?” To say this:

“Lenin repeated this argument in his discussion on the right tactics to apply during the near revolution of 1905. He mocked the Mensheviks for only wanting “pressure from below” which was “pressure by the citizens on the revolutionary government.” Instead, he argued for “pressure . . . from above as well as from below,” […] Lenin summarised his position […] by stating: “Limitation, in principle, of revolutionary action to pressure from below and renunciation of pressure also from above is anarchism.” This seems to have been a common Bolshevik position at the time, with Stalin stressing in the same year that “action only from ‘below'” was “an anarchist principle, which does, indeed, fundamentally contradict Social-Democratic tactics.”

Unfortunately, this is quite a misrepresentation of the segment being cited. On its face, this conflicts with rhetoric of nearly every Marxist movement and slogan. What happened to “power to the people”? Doesn’t power come from labor, or are Marxists simply liars? Well, to see why Lenin speaks in support of pressure from above, we have to understand what he was referring to in context.

This section of Lenin’s writing contains a lengthy examination of the First Spanish Republic, which arose in 1873, after King Amadeo abdicated in the face of a rebel attack.

At the time, Spain was a backward country with little industry and was, in the view of Marxist commentators, entirely unprepared for a socialist revolution and the complete emancipation of the working classes. With the monarchy gone and the die-hard monarchists refusing to take part in the revolutionary government, the country found itself in the middle of a democratic revolution.

The working class of Spain finally had a chance to assert its political power. The workers understood that by organizing politically they could speed up the breakdown of the barriers that were holding them back from full emancipation. To fail to participate would be to leave all political power in the hands of the owning classes.

The Bakuninists, however, asserted that all revolutionary action had to come from below and force itself on the structures above it. They rejected the idea of taking up posts in any revolutionary government, declaring that any government that didn’t deliver immediate socialism to the working class only existed to betray and deceive it.

Consider for a moment, what would happen if a government was formed from the bottom up, with the top never implementing anything “down” on to the people. What would be the point of a governing structure if it never worked towards the goals it was created for? If a governing body is elected, it is elected to represent the people, if this body then does nothing, it is representing nothing. A proper democratic governing body must be elected and take ideas from the masses, and then re-extend these ideas and goals back to the people. If a political structure is created to deal with poverty, or fascist vagrants, or anything of the sort, it gets that will from the people and must then exert the will onto the world. It is a dialectical process of the masses analyzing what they want and need, those needs being collected and gathered into an organized body, and then those needs being carried out back into society by the governing body. If the governing body never implemented any of the policies elected on, or never helped the people with the issues they had, it would be dead and utterly useless. For a government to achieve something, it must, necessarily, implement its’ will onto society.

This understanding of “top-down” is often conflated for simply undemocratic systems, systems where the will being implemented back onto society, is not from the society which it effects, something is “top-down” in popular consciousness, if it does not represent the will of the people, if the top of a governing body is in power without the support of the masses. We can see how confusing these two uses of the term “top-down” could cause issue. This is why Lenin called the principle of using only pressure from below, while renouncing pressure from above, to be an Anarchist principle. Lenin calls for both bottom-up representation and then top-down dissemination of policy arrived on through said democratic representation. He views a rejection of organization, rejection of any central authority, even a democratic one, as Anarchism.

A Marxist examination of the Spanish First Republic by Engels asserts that where the working class did rise up and take control of towns, the revolutionary governments of these towns – which were ironically often governed by Bakuninists – should have used their official positions to organize the people under them. That is, the power handed to them by the people, for the purpose of completing the democratic revolution, should have been used to organize the people to win that fight. At the same time, he critiques them for being a governing body despite denouncing governing bodies just prior to the revolution in Alcoy (“a manufacturing town of comparatively recent origin with a population of 30,000” at the time). Collected works on Lenin, Volume 8, pg. 478

“After the event [revolution in Alcoy] the Bakuninists began to boast that they had become “masters of the situation”. And how did these “masters” deal with their “situation”, asks Engels. First of all, they established in Alcoy a “Welfare Committee”, that is, a revolutionary government. Mind you, it was these selfsame Alliancists (Bakuninists), who, only ten months before the revolution, had resolved at their Congress, on September 15, 1872, that “every organisation of a political, so-called provisional or revolutionary power can only be a new fraud and would be as dangerous to the proletariat as all existing governments”. Rather than refute this anarchist phrase-mongering, Engels confines himself to the sarcastic remark that it was the supporters of this resolution who found themselves “members of this provisional and revolutionary governmental power” in Alcoy. Engels treats these gentlemen with the scorn they deserve for the “utter helplessness, confusion, and passivity” which they revealed when in power. With equal contempt Engels would have answered the charges of “Jacobinism”, so dear to the Girondists of Social-Democracy. He shows that in a number of other towns, e.g., in Sanlúcar de Barrameda (a port of 26,000 inhabitants near Cádiz) “the Alliancists … here too, in opposition to their anarchist principles, formed a revolutionary government”. He reproves them for “not having known what to do with their power”.

Again, this is what Lenin was referring to when he argued for pressure from above as well as from below. He was simply saying that people should do the jobs that they’re elected to do, instead of passively waiting for revolutionary action from below to force their hand at every point. This is quite different to what Anark implied when he said that Marxists prefer top down organization. And different to the context presented by the Anarchist Library’s use of that Lenin quote.

Not only that, but this situation mirrors the criticism from Engels found in On Authority, which I quoted earlier:

“When I submitted arguments like these to the most rabid anti-authoritarians, the only answer they were able to give me was the following: Yes, that’s true, but there it is not the case of authority which we confer on our delegates, but of a commission entrusted! These gentlemen think that when they have changed the names of things they have changed the things themselves. This is how these profound thinkers mock at the whole world.“

The Bakuninsts in practice, took power in governments, despite resolving at their congress just prior, that all such governments were oppressive institutions of the ruling class. Despite this, Engels isn’t concerned with whether or not it’s inline with their politics, rather he wishes they utilized their positions for good, and would have worked to dismantle the remaining reactionaries in the area instead the “‘utter helplessness, confusion, and passivity’ which they revealed when in power.”

In addition to all the similarities in structure, I would argue that projects claimed by Anarchists like “Rojava” are far worse than the reality of comparable Marxist projects, such as Cuba. This aligns with the reality brought attention to by Engels, that Anarchists do approve of taking power within certain governments, but they often do so poorly and their structures achieve very little real liberation. Even if we were to add in other projects mentioned like the Shinmin commune and the CNT-FAI the picture does not get any better for Anarchists, though those projects are a topic for another time.

Moving on from this very long section, lets address Anark’s claim surrounding Anti-Authoritarianism as non-western.

Is Anti-Authoritarianism Western?

Is JT claiming that “Anti-Authoritarianism is Western” a problem? Does it erase countless successful revolutions?

Anark poses that JT has forgotten about these revolts he (Anark) sees as successful, because JT doesn’t include Rojava or EZLN is his video. I believe that JT left these movements out intentionally. For one, JT notes specifically revolutions which have taken control of countries. None of Anarks examples have done this, so they categorically do not fit JTs criteria, which seems likely to be an intentional definition. At best, Zapatistas have established Dual Power, but are short of a full revolution. If you’re curious about Dual Power you can read a short work on the topic by Lenin here. In short, they have achieved a Parallel government but in no way have they overthrown the Mexican government, which is what a revolution would consist of. Even if we ignore this fact, knowing what we do about “Rojava” from the earlier sections, I think it is very understandable to leave the movement out of the discussion. It is likely an intentional absence due to their problematic position, not because JT has forgotten about Rojava, or doesn’t know about them, but rather precisely because he does that it would be left out.

In the larger discussion concerning “Anti-Authoritarianism” and its prevalence in Western culture as opposed to the world as a whole, there are two points to be made. The first, though a shorter point, is that “Authoritarianism” is Western philosophically and linguistically. It follows a long line of Enlightenment classical Libertarian ideology. Ideology that, is not universal especially outside of the West. Even when translated directly to other languages terms like Liberty and Authoritarianism may not have the same connotations. A Chinese Comrade has informed me that there is in fact no real term for “Authoritarianism” in Mandarin, with the closest term being 威权 + 主义 (authority) + (ideology), they stated that this carries a very different meaning to what “Authoritarianism” means in English. Though I was unable to find anything concrete on the linguistics front with regards to Liberty, as there are several unconfirmed rumors floating around as to how the term translates. I am unable to confirm the rumors as I’ve only ever lived in English speaking countries and am not a linguist in any form.

Even ignoring the philosophy and linguistics behind the term though, there are other reasons to see popular “Anti-Authoritarianism” as uniquely Western. The second and more important point I want to make is that many socialist countries which are labelled as Authoritarian, had large amounts of support both from their citizens and surrounding countries fighting against Capitalism. The Eastern Bloc was called such for a reason. Additionally, the very projects which Anark says are being erased by putting off “Anti-Authoritarian” rhetoric, are themselves supporters of said socialist projects. The Zapatistas are outspoken allies of several Marxist-Leninst projects, having close ties to Cuba in particular as I outlined earlier. Other projects which Anark claims are being “erased” would themselves be called “Authoritarian” upon genuine and honest investigation. If Cuba is Authoritarian to Anark, but Rojava is not, he is simply being dishonest. Whether that be with himself or us, I do not know.

Conclusion

In the end, much of this discourse is semantics. While semantics matter, they are not the area that I think is most important to discuss. In discourse like this there are often two levels of argumentation.

- What do we call a certain kind of things? and

- What is the reality of a this thing?

If we take the USSR for example. We can argue all day over what words to apply to it, but we will get nowhere if we don’t agree on the underlying structures that actually existed. We have to settle the base argument before we can even hope to address semantic differences in terminology. Often, I do think the term authoritarianism is a bit overused and applied poorly. But in my opinion this is primarily because the term is applied to things which do not fit what I would consider authoritarian, and only secondarily because I think the term authoritarian in particular is a flawed way of talking about existing structures. I would much rather address the reality of how a society is organized than discuss the terms we use to describe it but unfortunately we don’t always have the luxury of doing so, as throwing such terms at political projects usually shuts down all conversation on the specifics. Overall the term authoritarian is misapplied to societies which were organized as proper democracies and were huge improvements over what came before, and shuts down discourse instead of opening it up to an analysis of the real conditions and organization at play. This is why I find it distasteful and generally discourage its use. I do think its very possible to be “authoritarian”. I’d say it’s a fair label to apply to capitalism, a brutal and undemocratic system, but I don’t think it is a fair assessment of places like Cuba or the USSR, historically speaking. We should watch our usage of terms applied to historical movements, in light of the realities of these movements, and be careful to not shut down discourse, but rather bring up the reality and work to find solutions through specific and constructive criticisms.