Every year, the Economic Intelligence Unit releases the Democracy Index. This index claims to rank countries by how democratic they are. But how credible is it?

The first thing we notice when we look into it, is that the Democracy Index is put together by the same organization that owns The Economist magazine. This isn’t an independent group of democracy researchers. It’s an organisation with its own ideological agenda: specifically the promotion of Liberal Capitalism.

Of course, it would be unfair to write the Democracy Index off purely on the basis of who puts it together. Now that we’ve identified their potential bias, it’s our job to examine whether or not the Democracy Index is compiled in a biased way, or whether it tries to be an objective measure of democracy.

To do this, we’ll be looking at the report they released in 2022, which contains its methodology, as well as the conclusions that the researchers drew from the study.

One of the first things we notice about the report is the sheer number of pages that it devotes to the Russia Ukraine war. There were many conflicts going on in the world in 2022. There was the Ethiopian Civil War, the continued attacks of the Israeli apartheid regime against the people of Palestine, the civil war and Saudi bombing campaign in Yemen, and the fight against the military junta in Myanmar to name a few.

But the Economist picked out the Russian invasion of Ukraine as being so important to global democracy that it dedicated 11 of its 81 pages to the topic.

Arguably, the fight of the Burmese people to overthrow the military junta, and finally establish liberal democracy, is as important, if not more important, in terms of global democracy than the war in Ukraine. It must surely be a coincidence that the Ukraine war, which is of such great interest to Western capitalism, is examined in great detail, while the Myanmar conflict is almost completely ignored.

In the report’s examination of democracy in Russia and Ukraine, we find our first example of The Economist lying to try and push a political agenda.

According to the report: “A key difference between Russia and former Warsaw Pact countries, such as the Czech Republic or Poland, is that Russia never had any prior experience of democracy, except for a brief moment between the February and October revolutions of 1917.”

This is a very strange statement. The Economist might not approve of the model of democracy that existed in the Soviet Union – I’d be surprised if it did – but to deny that democracy existed in Soviet Russia is an outright lie.

The Economist can only do this by framing liberal style democracy as the only valid model of democracy. We see that explicitly when they say that Russia only “had democracy for a brief moment between the February and October revolutions”. This was the period where the Constituent Assembly existed. The Constituent Assembly was a parliamentary style democracy, the ideal model if you want capitalism to develop, but far from the only model of democracy available.

If you want to see a video about how democracy was structured in the Soviet Union, this one is a good introduction.

I’m not going to do a full debunking of the report’s views on Russia and Ukraine, as that could fill a video of its own, but this was an important point to highlight, as it reveals the narrow way that the Economist is defining democracy when it compiles the Democracy Index.

We’ll see this theme recur again when we examine the criteria that countries are judged on.

But first, question time: Which continent is Mexico part of?

If you said North America, every atlas and encyclopedia in the world would agree with you, but the Democracy Index wouldn’t. To the Democracy Index, Mexico belongs to Latin America while North America is made up of only the United States and Canada, which, incidentally, it classifies as the most democratic region on Earth.

If they’d consciously decided to split the Americas up into exploited and exploiters, they couldn’t have done a better job. There doesn’t seem to be any reason to leave Mexico out of the North American group, unless you’ve decided beforehand that there’s something which separates it from the rest of North America.

Mexico is obviously less white, Spanish speaking, and highly exploited by the US, which are all ways that it’s similar to the other Latin American countries. And yet, it’s still part of North America. Deciding to other it for Western readers is an ideological choice. It’s a way of creating psychological distance between the rich, white part of North America and the rest of it.

The next issue that’s worth highlighting is the way that the Economist gushes over US democracy in its conclusions, which are all stacked at the front of the report, before the methodology.

To quote the report: “The US score for political participation remains among the highest worldwide and stands at its highest level since the Democracy Index first launched in 2006. American voters continue to exhibit strong political engagement. Turnout during the November 2022 midterm elections was among the highest on record, with nearly half of eligible voters casting ballots.”

It seems strange to highlight voter turnout when objectively the US lags far behind many other nations in this regard. According to information released by Pew Research in 2022, the US scored 31st in the world for voter turnout, which is hardly something to write home about.

In fact, later on in the report, the Democracy Index itself highlights the much higher voter turnout that it would expect to see in what it calls “established democracies”.

“A high turnout is generally seen as evidence of the legitimacy of the current system. Contrary to widespread belief, there is, in fact, a close correlation between turnout and overall measures of democracy—that is, developed, consolidated democracies have, with very few exceptions, higher turnouts (generally above 70%) than less established democracies.”

Yet, the US struggles to get voter turnout near that level for a presidential election, nevermind a midterm.

There’s another problem here as well though. The Economist is presenting us with its finding that established democracies have a 70 percent or higher voter turnout, but it actually drew this conclusion before it wrote the report. Question 27 in their test measures the turnout for national elections, with countries scoring the highest mark if they have over 70 percent voter turnout. So the conclusion that true democracies have a 70 percent or higher voter turnout is actually an assumption that’s built into the test, with countries that meet that standard receiving more points.

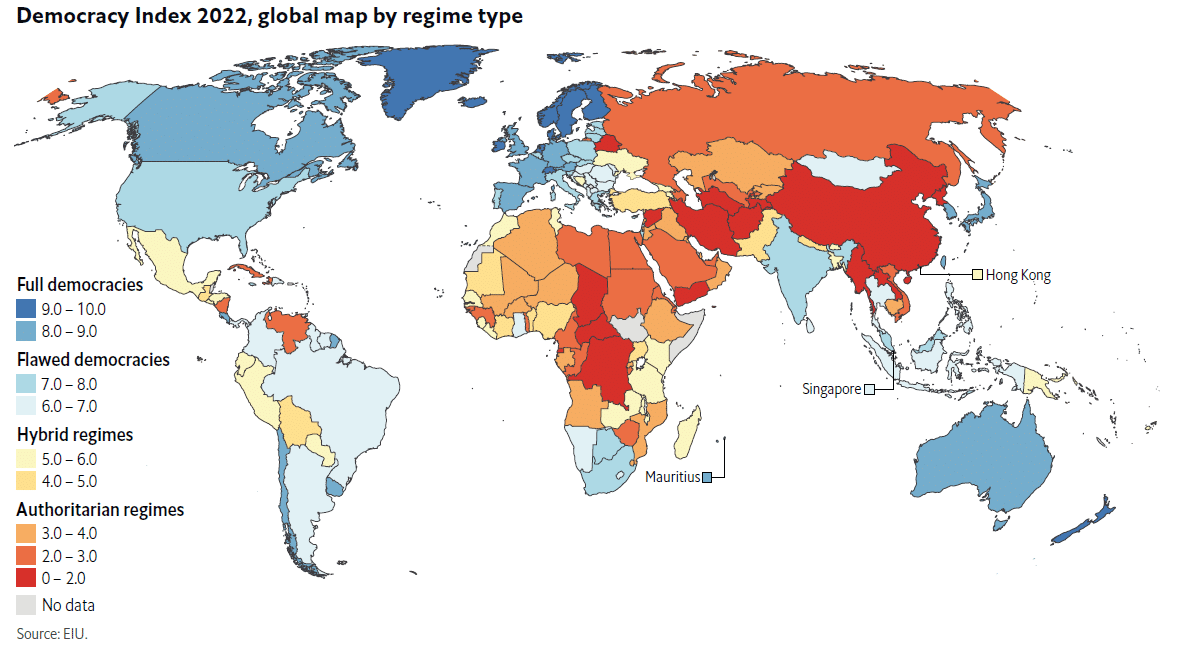

Before we go on and examine the other criteria that the report used to rank countries in more depth, it’s worth looking at the four groups that it ranks countries into based on their scores.

The first category are what it calls “full democracies.” These are countries in which not only basic political freedoms and civil liberties are respected, but which also tend to be underpinned by a political culture conducive to the flourishing of democracy. The functioning of government is satisfactory. Media are independent and diverse. There is an effective system of checks and balances. The judiciary is independent and judicial decisions are enforced. There are only limited problems in the functioning of democracies.

According to the report’s definitions, flawed democracies have a little less of all this good stuff, and hybrid democracies have even less still.

Then we get to the definition of authoritarian “regimes”, and oh boy are there some ideological beliefs packed in here.

According to the Economist: In these states, state political pluralism is absent or heavily circumscribed. Many countries in this category are outright dictatorships. Some formal institutions of democracy may exist, but these have little substance. Elections, if they do occur, are not free and fair. There is disregard for abuses and infringements of civil liberties. Media are typically state-owned or controlled by groups connected to the ruling regime. There is repression of criticism of the government and pervasive censorship. There is no independent judiciary.

The problem with this definition is that it assumes that well functioning democracies follow the model of liberal democracy. This means that some of the most democratic countries on Earth, such as Vietnam and Cuba, get classed as authoritarian “regimes”, alongside autocracies like Saudi Arabia and Oman.

If you did a double take at me calling Cuba and Vietnam highly democratic, then bear with me because I’m going to back up my claims. For now, though, let’s just say that socialist models of democracy look different from those that exist under capitalist states.

If we base our understanding of what democracy is by looking at the surface level features of liberal democracy, we can end up misclassifying other democracies.

In fact, over the last seventeen years, the Democracy Index classing these countries as “authoritarian regimes” has done a lot to promote the idea that these countries aren’t democratic.

Without further ado, let’s dive into the questionnaire used to classify each country. There are a lot of questions, so I’m going to skip the uncontroversial ones and only bring attention to the ones that are problematic.

As it would happen, the very first question in the survey is steeped in liberal bias. It asks whether elections are free, and we’re told to score the country zero if it’s a one-party state. On the face of it, this might seem uncontroversial but it actually defines democracy in a very limited way: it says that any system which isn’t a multi party, liberal style democracy is undemocratic by default.

To demonstrate why this is wrong, let’s look at the way democracy functions in Cuba, which is a one party state.

On its lower level, Cuba is divided into 169 municipal districts, which oversee governmental, economic, and social activities within their territories. In total, roughly 12,500 municipal seats are available during each election.

All voters are registered automatically, and for free. Voting isn’t a legal requirement but it takes place on a Sunday, to make sure that the maximum number of people who want to participate are able to.

Candidates aren’t nominated by any political party and aren’t allowed to put themselves forward for nomination, which makes it more difficult for those seeking power to chase public office. Instead, all candidates are nominated by people in their communities.

The elections themselves are funded by the government, with candidates not allowed to accept donations or spend extra money campaigning.

The campaigning consists largely of candidates’ profiles being posted up in windows around the neighborhood, to tell voters about their character and experience. Candidates aren’t allowed to make any promises to voters about the policies they’ll pursue once they’re in office, eliminating the risk of candidates bribing their way into office with promises that they can’t or won’t deliver on.

In order to get elected, a candidate must receive at least 50 percent of the votes. If nobody manages to achieve that in the first round of voting, there’s a run off vote between the two candidates who receive the most votes in the first round. This is in contrast to the plurality voting that exists in places such as the UK, where a candidate in South Belfast won the right to become an MP with just 24.5 percent of the vote in 2015.

As we can see, despite Cuba being a one-party state, strong democracy exists at the municipal level. It merely takes a different form than that seen in liberal countries; some would argue it’s a better form: one that keeps money out of politics and puts the power in the hands of local communities.

Elections to the provincial and national assemblies are structured a little differently.

Candidates are put forward by the country’s mass membership organisations, such as the Federation of Cuban Women, the National Association of Small Farmers, the Confederation of Cuban Workers, the Federation of Cuban University Students, the Federation of Highschool Students, and the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (which are the local neighborhood organizations.) Almost all Cubans are members of at least one of these organisations, and many are members of multiple.

Each candidate runs unopposed but still has to receive at least 50 percent yes votes in order to be elected. If they’re rejected by the public, a more acceptable candidate has to be put forward.

This system was set up to ensure that candidates from a wide variety of backgrounds get elected to national and provincial positions. As a result, it’s common for women, young people, racial minorities, and queer people to have seats in the National Assembly.

Most politicians aren’t paid for their work in Cuba, which minimizes the risk of corruption in the nomination process. Even National Assembly members still keep their regular jobs, while doing their work as politicians for free.

So, to sum up, candidates are either put forward by their neighbours or by the mass membership organizations that represent most Cubans. Voter registration is free and automatic. Candidates aren’t allowed to spend money on campaigning and aren’t allowed to try and bribe voters with policy promises. There’s no financial incentive for people to chase public office. And no candidate is elected with less than fifty percent of the vote.

We might ask whether there are better models of democracy than the one Cuba practices, but to say that democracy doesn’t exist in Cuba, simply because it’s a one party state, is absurd. Yet the Democracy Index criteria requires us to score it as zero for this question, solely on that basis.

The next question the Democracy Index asks is whether elections are fair. However, it says that if the country scored zero in the last question, then we should score it zero here too. It doesn’t matter that in Cuba, for example, all vote counting is overseen by volunteers, and happens publicly in the community where voting took place. If the country’s a one party state, we have to score it zero. The scoring for this question has nothing to do with whether or not elections are fair, and everything to do with whether the country follows liberal style, multi-party competition.

The next concerning question is number seven: Is the process of financing political parties transparent and generally accepted?

There’s a big problem with this. Wildly different forms of financing political parties can be generally accepted once they’ve become normalized in a society. In a society such as Cuba, for instance, the introduction of private financing into election campaigns would cause an outcry. Whereas in the US, people are so used to candidates spending billions of dollars on campaigns that it’s generally accepted, even if most people would like it to be different.

Hopefully you can see the problem with this. In some countries candidates can be financed by private interests, who use that leverage to gain favours. This undermines the very idea of democracy, and yet it can be generally accepted because it’s become normalized. So even a country like the US or UK can score full marks on this question, despite political candidates being beholden to monied interests.

Next we have question nine: Are citizens free to form political parties that are independent of the government? Again we have the built-in assumption that a democracy has to be a system of multi-party competition.

It’s the same in question ten, which asks: Do opposition parties have a realistic prospect of achieving government? That’s another zero for non liberal countries.

We’re only a sixth of the way through the questions, and it’s already clear that the criteria are designed to promote liberal style, competitive, multi-party democracy as the only legitimate kind.

Question 25 is another interesting one, not because of the question itself but because of the scoring criteria. The question asks about the level of public confidence in government, with a country being awarded the highest marks if the public has 40 percent or more confidence in the government. Anything between 25 and 39 percent will get a country half marks, and anything below that earns a zero.

When there are governments in the world with a trust rating from their citizens of over 80 percent, setting the bar at 40 percent seems very low indeed. But what this low bar does is allow countries such as Germany, Canada, the US, France, and Australia to score full marks, instead of being out scored by China.

In China, the level of trust in government was 89 percent in 2022. But not to worry, the US scored just as many points in the Democracy Index survey with its unimpressive 42 percent trust level from its citizens. That means the US is receiving the same marks even though US citizens trust their government at less than half the rate that Chinese people trust theirs.

Some will argue that countries like China don’t count because they’re so-called “authoritarian regimes”, which supposedly brainwash their citizens. But if the answer to this question isn’t actually helpful in determining which countries are democratic, why is it in the survey?

The fact is that independent research shows that Chinese citizens trust their government more than twice as much as US citizens trust theirs. If The Economist thinks that trust in government is a valid indicator of democracy, it should be scoring this question impartially, not setting the scoring criteria at a level where the underperforming liberal democracies can get full marks.

The next question pulls the same trick, when it asks about trust in political parties and sets the bar so low that countries with wildly different trust levels score the same. Then we’re onto something quite different.

Questions 37, 38, and 39 ask whether a country’s citizens think that the country should be run by a strong leader who can bypass parliament, whether it should be run by the military, and whether it should be run by experts rather than politicians.

Obviously, if citizens believe these things, it’s a sure sign that they don’t have faith in their country’s process for electing politicians and distributing power to them. What’s interesting about these questions is the scoring criteria though. For the question about whether society should be run by a strong leader who can bypass parliament, a country scores full marks if under 30 percent agree with this. But for the question about whether the military should run society, a country gets full marks if under 10 percent of the population agree. For whether society should be run by experts, the threshold is 50 percent.

The report doesn’t give any justification for the scoring criteria of these questions, so we can only guess as to The Economist’s reasoning.

Looking at the World Values Survey data that the report based its scoring on, it seems like they just took the average and chose a slightly lower number when awarding full marks. 33.3 percent of people globally said that it was good to have a strong leader who could bypass parliament and elections, so The Economist set the bar at 30 percent. 22.7 percent globally said that the military should rule their country, so The Economist set the bar at 10 percent. And 56.1 percent globally said that experts should run their country, rather than elected politicians, so The Economist set the bar at 50 percent.

There are worse ways to score these questions, I guess, even if it does feel arbitrary. But when a full 49.9 percent of the population wants experts to run society instead of elected officials, it seems weird to give the country full marks for democracy.

Questions 44 and 45 ask whether there is free electronic and print media. Countries are supposed to be marked down if media ownership is diverse but government controlled media is heavily favoured, or if there’s a high concentration of private ownership. The clear inference is that media only serves democracy well when it’s privately owned but hasn’t formed into monopolies.

There are some problems with this line of reasoning however. It doesn’t matter how many separate capitalists own the news media, they’re always going to promote the same range of pro capitalist views and politicians, no matter the opinions of the electorate.

Pew Research has found that 36 percent of people in the US held a favourable view of socialism in 2022. Yet how much of US news coverage spreads favorable views about socialism? Is it anywhere near 36 percent? Not even close.

But according to the 2016 book Who Owns the World’s Media?, the US has some of the least concentrated ownership of news media in the world.

The truth is that spreading out the ownership of the media amongst a larger group of capitalists doesn’t result in having media that accurately reflects the views of the majority, or which promotes their interests.

The media in every country promotes a worldview that benefits the class which controls it. State aligned media in Russia promotes the worldview that helps its oligarchs, while state controlled media in China promotes the socialist worldview, since it’s a worker controlled, socialist state.

It’s not the diversity of ownership in media that changes the interests that it promotes, it’s the class character of the actors who control it.

China and Cuba are as likely to let liberals spread pro-capitalist propaganda in their state media as the privately owned New York Times or the Daily Mail are to let Marxist-Leninists spread communist talking points in their pages.

The other issue with these questions about media ownership is that they presuppose that capitalism is necessary for democracy. Without capitalism, there can be no private ownership of the media, let alone diverse ownership.

Conclusion

The Economist tries to pretend that the Democracy Index is a neutral assessment of democracy around the world, while actually there’s a strong ideological bias to its ranking. It strongly favours liberal democracy and penalises other models of democracy.

By and large, the liberal media lets them get away with this deception by never examining the nature of the Democracy Index when they report on its findings.

Its bias isn’t surprising, though, given that the Economist is a longtime propaganda tool for liberal capitalism. In 1915, Vladimir Lenin famously called the magazine “a journal that speaks for the British millionaires.”

In a world where capitalism is increasingly in crisis however, in a world of climate collapse and profit rates falling towards zero, unquestioning acceptance of liberal propaganda is something that none of us can afford to do, unless we want to see society collapse.

Okay guys, that’s the end of the article. Remember to share it with anyone who might be interested. Until next time.